Mary Magdalene:

Separating Fact from Fiction

Robert Myles, Dean of Research and Associate Professor of New Testament, Wollaston Theological College, University of Divinity

On July 22, the church celebrates the feast of Mary Magdalene. Mary’s image has been subject to serious distortion, making her longer reception history a good case study in biblical (mis)representation.

Most notable is the conventional presentation of Mary as a repentant sex worker, a habitual identification going back to at least the sixth century. This conflation involves the Magdalene being merged with other biblical characters, including Mary of Bethany (John 12:1-8), the unnamed repentant ‘sinner’ from the city (Luke 7:36-50), and sometimes the unnamed woman caught in adultery (John 8:3-11).

Popular culture has also frequently sexualised Mary, sometimes in contrast with Jesus’ asexualised mother the Virgin Mary. In Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), for instance, Mary Magdalene is depicted as an unveiled, tattooed, seductive, and promiscuous woman who turns to sex work because Jesus refuses to marry her. Whether portrayed as a scantily clad courtesan in Bible films, or as Jesus’ lover in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code. However, the Gospels interestingly have nothing to say about her sexual past.

In the biblical accounts, Mary is depicted as one of the women who travelled with Jesus, as someone previously possessed by seven demons (Luke 8:2), and an important witness to the crucifixion (Matt 27:56; Mark 15:40; John 19:25) and burial and empty tomb traditions (Matt 27:61; 28:1; Mark 15:47; 16:1, 9; Luke 24:10; John 20:1, 11, 18).

Image: Mary Magdalene (c. 1598) by Domenico Tintoretto, depicting her as a penitent (Wikimedia commons)

Another common distortion is the assumption that Mary’s nickname, ‘the Magdalene’, means she hailed from a place called Magdala. In Aramaic, the term means ‘the tower’. While a tradition associating ‘Magdalene’ with her hometown goes back to at least the fourth century, some early Christian writers thought of it more as a nickname indicating her as a ‘tower’ of faith (e.g., Jerome, Epistles 127).

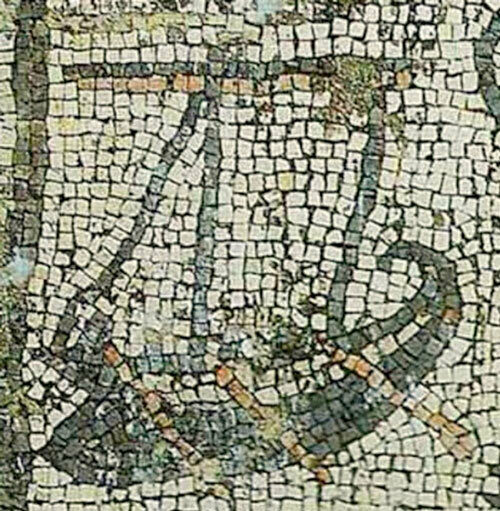

Today, Mary is frequently associated with the modern site of Magdala, on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. Archaeologists have excavated what appears to have been a bustling port city from around the time of Jesus with strong connections to the exploitation of the lake’s fisheries.

Image: Detail of a first-century CE mosaic discovered at Tarichaea (Magdala) (Wikimedia commons)

However, it is unlikely Mary had any connection to this place. During the first century, this site was named Tarichaea, not Magdala. Moreover, early Christian writers who did interpret Mary’s nickname as a reference to her hometown (e.g., Eusebius, Ad Marinum 2.9) understood her as coming from a small, unimportant village, not a bustling city like Tarichaea.

Quite where Mary hailed from remains a matter of scholarly debate. If her nickname did reference a specific location, then several places in Palestine took on the name Magdala, particularly locations associated with a fishing tower or fortification.

What remains beyond dispute is that the Gospels make no comment on Mary’s sexuality or profession. Whatever else we might say about her, she was an important enough member of Jesus’ inner circle to be named by the Gospels, and she played a prominent role in the organisation of the early movement as first witness to Jesus’ resurrection.